Beginning as early as 2009, a series of memes began circulating on social media that were intended to demonstrate in comical ways the lack of interest or care someone felt on a particular day or about a particular issue. Colloquially, they’re the “Look at all the fucks I give” memes, with the unmistakable implication that the poster gives none. (That the original version was an animated .gif of anti-fascist icon, Maria, from The Sound of Music is terribly ironic in retrospect, as will become clearer below.)

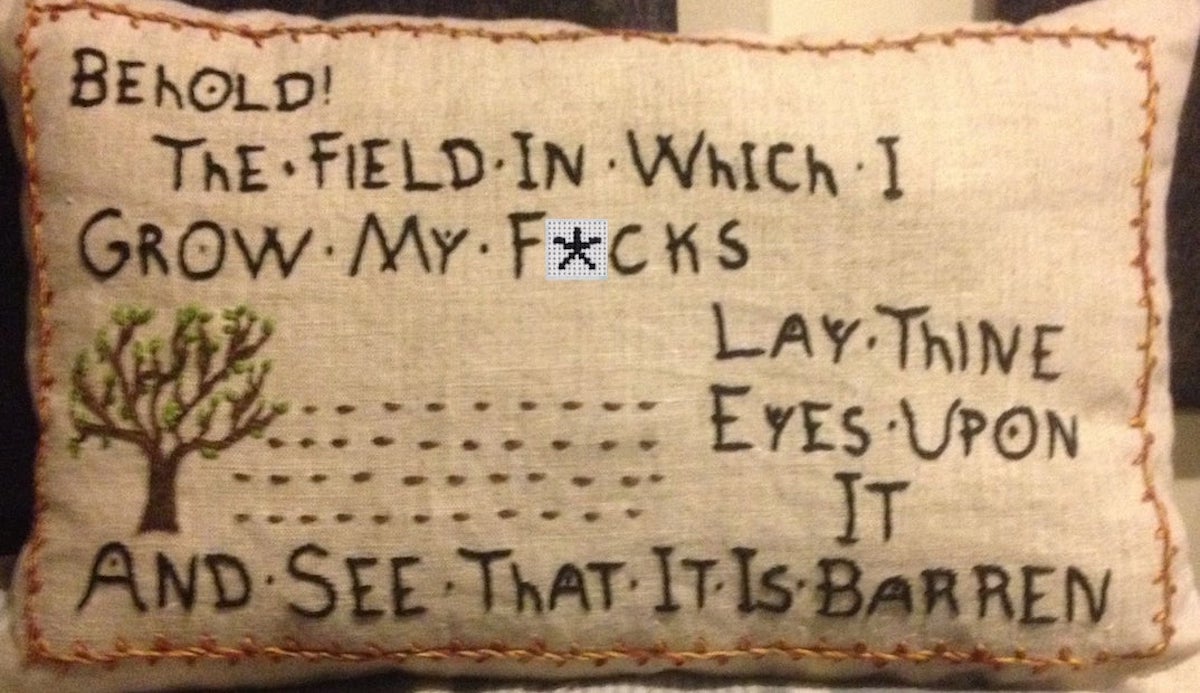

The circulation of “Look at all the fucks I give” memes has only intensified in the subsequent decade, and it has become recognizable enough as a meme to appear in other media as well. In 2018, Hank Green’s New York Times bestselling debut novel, An Absolutely Remarkable Thing, included the following passage: “Manhattan is less legit than it once was, for sure, but this is still the city that never sleeps. It is also the city of ‘Behold the field in which I grow my fucks. Lay thine eyes upon it and see that it is barren’” (pg. 8). That specific version of the sentiment is now a fixture in the ever-roiling meme library, and it also appears in whimsical cross-stitches and embroidered throw pillows on Etsy.

In recent years, demonstrating detachment has proliferated well beyond the meme-o-sphere, as well. In 2016, blogger and self-help guru Mark Manson published a New York Times bestseller bearing the provocative title, The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck. The title is misleading given what Manson advocates, but it picks up nicely on the tone of the meme. Likewise, two years after Manson’s book came out and just three months before Green’s novel was published, Melania Trump sparked controversy when she arrived in Texas to visit children in detention camps on the southern US border wearing a jacket that said “I DON’T REALLY CARE DO U?”

My goal here is not to exhaustively document the apparent lack of care in contemporary culture. I don’t actually believe that the prevalence of the sentiment is true to any significant degree. In my experience, the people most apt to use say they don’t give a fuck or don’t care actually tend to care a great deal. Which is why I think it’s time to consider retiring the phrase(s), and frankly, the whole attitude.

Before I get to that, however, I want to note two phenomena about the fallow grounds of caring—the first being the evolution of “I don’t care” from a social media joke into something of a slogan. You can see it most clearly in Green’s use of the meme to describe Manhattan, but its equally obvious in Trump’s interview, in which she said of her jacket that is was “for the people and for the left-wing media who are criticizing me. And I want to show them that I don’t care.” In both the Manhattan and Trump examples, not caring isn’t enough. Boldly demonstrating that you don’t care is the point. “I don’t care” is not just a clever quip, it’s an identity marker. It’s who you are and who you want people to see you being. Not for nothing in Trump’s case, it comes straight out of her husband’s media strategy playbook.

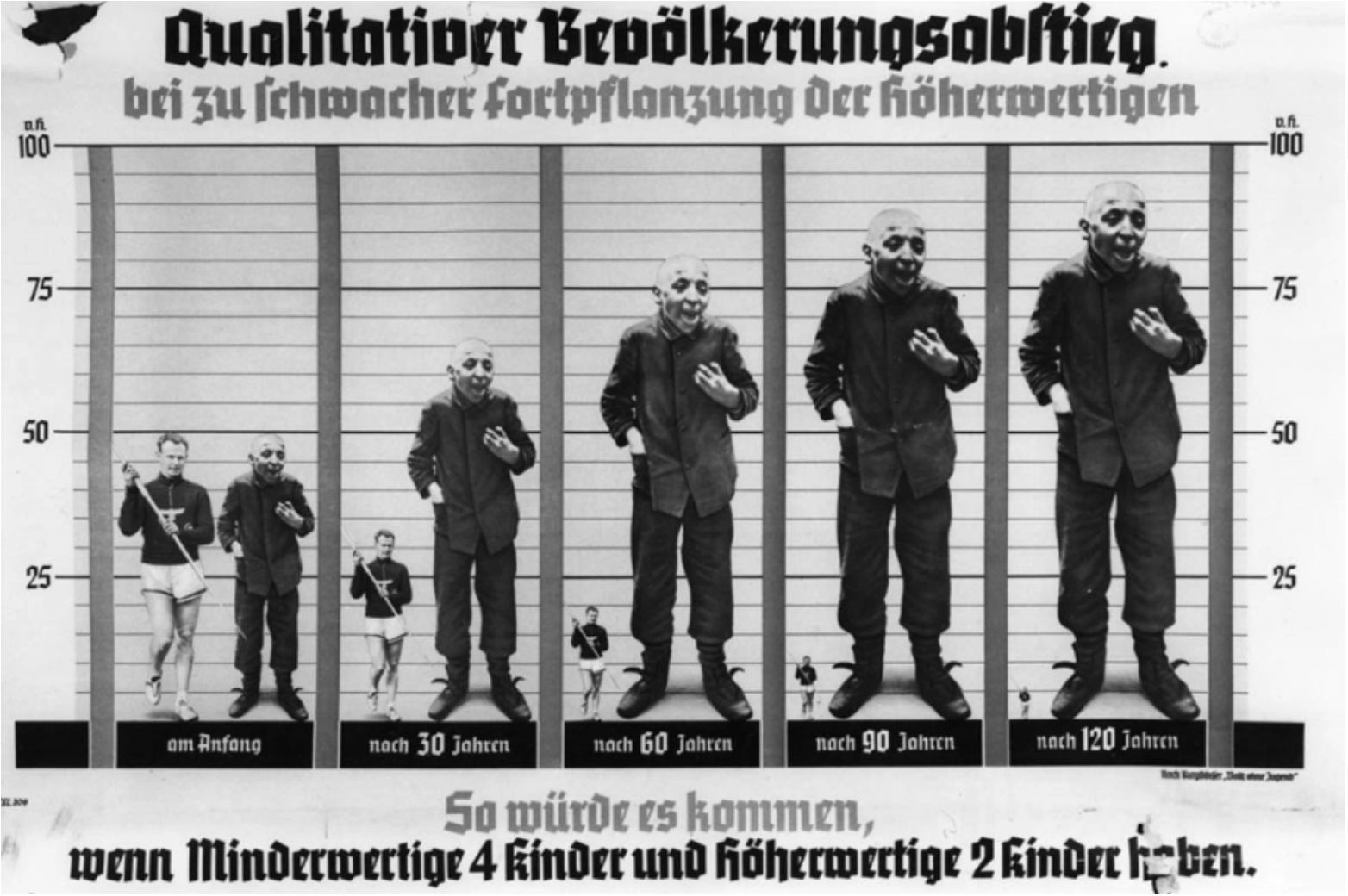

The second related phenomenon I want to note is a historical one. A century ago, Fascism was on the rise in Italy. Not just vaguely authoritarian groups, mind you—the literal Fascists. In about 1920, supporters of Benito Mussolini and Gabrielle D’Annunzio (a Fascist intellectual and early party leader), recycled a WWI song called Me Ne Frego to celebrate the growing vitality of the Fascist movement. “Me ne frego” translates roughly to “I don’t give a fuck.”

Before long, Mussolini had adopted the slogan “me ne frego” as a guiding philosophy of Fascism. It symbolized for Mussolini and his Fascists the drive to live boldly and daringly without regard for the consequences, which might even include death. For the Fascists, “me ne frego” encapsulated a worldview that venerated speed, masculinity, violence, and action.

“Me ne frego” was an attitude.

I mean “attitude” in a technical, rhetorical sense. I’m borrowing the term from Kenneth Burke, who was a writer, literary theorist, and rhetorician in the 20th century. In fact, Burke was beginning his career in Greenwich Village at almost exactly the same time that Mussolini and D’Annunzio’s supporters were reworking their Fascist ditty.

Burke is surely not the only person to think and write about attitudes, but he was thinking and writing about them at the same time the Fascists were in power and in relation to the Fascists. And while his concept of attitudes can be complicated, we don’t have to go into all its complexities for it to be useful.

In Contemporary Perspectives on Rhetoric: 30th Anniversary Edition, Sonja K. Foss, Karen A. Foss, and Robert Trapp explain attitudes. Quoting Burke’s A Grammar of Motives, they note that attitude is “‘the preparation for an act, which would make it a kind of symbolic act, or an incipient act.’…In other cases, an attitude may serve as a substitute for an act—as when, for example, ‘the sympathetic person can let the intent do service for the deed’” (pg. 200).

In short, attitudes prepare us to see the world from particular perspectives and act in certain ways as a result. Or at the very least, attitudes prepare us to demonstrate to others that we share their values. So when I say “me ne frego” was an attitude, what I mean is that it prepares people who think of it as a guiding philosophy to act and perform in certain ways. For the Fascists, it literally prepared them to try to overthrow societal conventions and norms, commit acts of violence, and commit themselves to death if necessary to serve the Fascist cause. (Incidentally, they didn’t really have much of a cause beyond “be fascist.” Of course, they claimed to have a cause, but it was never achievable.)

There’s one other point worth borrow from Burke, and then I’ll set him aside. In another of his books, Attitudes Toward History, he helps us see why language and symbols are so important in the development of attitudes. He notes in his introduction that “a group’s routines can become its rituals, while on the other hand its rituals become routines. Or, otherwise put: poetic image and rhetorical idea can become subtly fused—a fusion to which the very nature of poetry and rhetoric makes us prone” (pg. xii).

Let me translate: we build our attitudes through language and symbols, and in particular through the repetition of certain language and symbols. At first, certain words, slogans, catchphrases, and poetic images seem (to us) to explain the world. But eventually, through repetition, they become the limits on the possible ways we are able to see the world. And how we see the world prepares us to act in certain ways.

So back to the barren meme fields of “Look at all the fucks I give”—which again, is none. As I noted above, there are a variety of ways people who use the memes and the “I don’t care” attitudes do it—often, for instance, sarcastically. But as the history of the phrase hopefully makes clear, “I don’t care” nevertheless coaches particular attitudes that persist beyond the joke itself. “I don’t care” prepares people to see and think—and eventually act—in particular ways.

What concerns me particularly is the sloganized version of the sentiment that is so nicely highlighted by the Melania Trump example above. Whatever her intention, her coat coached a particular attitude. It prepares her to see every action as one of provocation, and it prepares us—all of us—to see every one of her actions through the same lens. Even when she’s visiting kids in detention camps. Once we are prepared—once we have adopted the attitude—provocation becomes the point even in situations where the point should be (and is supposed to be!) care.

Ultimately, in a media environment where context is often lacking, where fascist and nationalist radicalization is rampant, and where proto- and neofascist groups thrive on disaffection, it’s far easier to hear “I don’t give a fuck” as “me ne frego” than as “I’m just kidding,” whatever the initial intent may be. Given that reality, I think anyone who doesn’t sympathize with fascists—old or new—would be wise to abandon the meme and its attendant attitudes. Fascists won’t—the better to identify them by. But more importantly, given how much we need care in the world right now, I think we’re wise to invest in giving a fuck.

Initially posted at: https://dissoitopoi.home.blog/2020/01/03/maybe-lets-leave-i-dont-care-to-the-fascists-yeah/